It isn’t much a of a stretch to call Cynthia Loyst a “renaissance woman”. Currently one of the hosts on CTV’s THE SOCIAL, Cynthia has been working both in front of the camera (including hosting duties on Space’s INNERSPACE) and behind the scenes ( producing as well as hosting City TV’s SEX MATTERS & SEX TV) as one of Canada’s most well-known and respected media personalities. She’s been a keynote speaker and guest lecturer at colleges and universities. She’s received numerous awards and commendations for her work in sex-education and is also a member of SIECCAN (The Sex Information and Education Council of Canada) and a graduate of The University Of Michigan’s sex education program. And she’s not done yet, as she’s embarked on her most ambitious project yet: Find Your Pleasure.

In her words, FYP is ” a space dedicated to candid talk about love, sex, and the relationships that mean the most to us. And because pleasure is about so much more than great sex, it’s also about sensual living – and the everyday joys that we can all be thankful for. ”

In between recent speaking engagements and her daily gig with THE SOCIAL, I was able to get some time to talk to Cynthia about life and pleasure – where to find it, how to get it, as well as working it into one’s regular routine.

What was the impetus to start FYP?

Well, when we first launched The Social, I had just given birth a few months before hand, so I was not only sleep deprived but very hormonal. Even though I loved working on the show, I also felt quite conflicted about leaving my young son every day. I was also rushing around trying to be AMAZING at everything: I wanted to be an amazing host, I wanted to be an amazing partner and, of course, I needed to be an amazing mom. And inside, I felt miserable.

It all caught up to me when a few months into working on the show, I had a minor panic attack live on the air. No one knew, and I didn’t tell anyone even afterwards but it was a real wake-up call for me.

The thing was, logically, I knew there were all kinds of things in my life to be happy about and thankful for. But I was drowning in “must-dos” and “should-dos” and general ennui about life. I realized that I couldn’t remember the last time I did something I loved JUST FOR ME. When I started asking my friends about this, I discovered it was the exact same thing for them. So I started to do a deep dive on pleasure and realized that it is a super fascinating and highly complex topic. And that eventually led to the website.

The launch party for Find Your Pleasure, February 8, 2017, held at Her Majesty’s Pleasure.

Sexuality forms a large component of FYP’s coverage. While we’ve become very open in discussing sex, as far as gender identity and equality, we still get squeamish when talking about the act itself. Do you still see self-repression among the masses, or are we finally getting over the hump?

In some ways the conversation around sexuality and gender has really progressed…I’m part of an online mothers’ group in my ‘hood and I’m so happy when I see them often sharing articles about sex education or about transgender youth. But in some ways, we are still so far behind. I have written an advice column for years and I still get the same types of questions over and over again which basically circle around this idea of “normalcy.” People are super concerned if they are having the “right” kinds of sex or “enough” sex or making sure that their fantasies or desires aren’t too out there. There’s the side that we think we should show to the world and the side that we show to a lover and then there’s the side that we only show to ourselves. If there’s one thing I hope that I get through to people is that everyone is unique. As long as you approach sexuality with the safe, sane and consensual mantra, the most important thing is to find out what pleasure looks like to you.

You lead a very busy life. How do YOU juggle all of that and still find the time to take part in life’s simple pleasures?

I have to shut down sometimes. I just got back from a 9-day cruise and I just turned off my phone. It was hard but it was also so rejuvenating. But I also have recently been researching about other people’s morning rituals and trying to come up with my own. Like, did you know that Benjamin Franklin used to take an “air bath” every morning? I know you’re wondering: what the heck is that? He would go out into the cold air – naked – and wander around (I’m assuming he had no neighbours or maybe he was an exhibitionist?) and then slip back into bed for an hour to have another short nap before starting his work for the day. I like the idea of having a little daily ritual to ground myself for the day. I highly doubt mine will look like that though.

The simple things, the little pleasures in life – which ones get you through your day?

My morning coffee that I make every morning from fresh beans and sprinkle with a dash of cinnamon. Getting outside and going for a bike ride along the lakeshore. Painting rocks with my son and just listening to his sweet, crackly voice. Playing board games with my other half or having a scotch with him at the end of the day. Cooking strange recipes. Going for long walks in the woods. Getting to bed early to read or to just luxuriate in the coziness of it all. Reflecting at the end of a day on everything that I am grateful for.

What are the plans for FYP’s expansion?

I want to start a pleasure revolution! I have been loving doing speaking engagements and hope to one day write a book. I think pleasure has often been seen as the bad cousin of happiness. I’m here to preach the importance of pleasure because it is intimately connected to happiness – you can’t have one without the other.

Cynthia Loyst can be seen on THE SOCIAL weekdays (and Saturdays) on CTV and CTV TWO – check local listings for times. She can also be heard Wednesdays mornings as Virgin Radio Toronto‘s weekly sex expert.

FIND YOUR PLEASURE can be found on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram.

Published February 21, 2017 on blumhouse.com

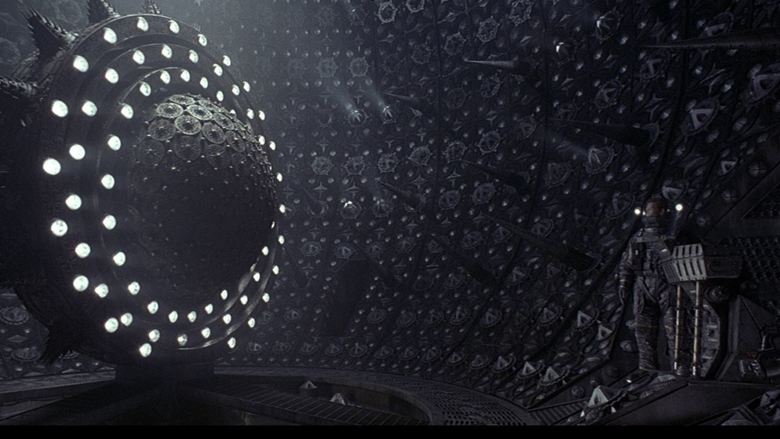

Published February 21, 2017 on blumhouse.com NIGHTBREED: A”no-brainer” and long overdue. Clive Barker’s 1990 cult classic has been screaming for a toy line for decades. With a newfound appreciation among horror fans, and a restored Director’s Cut that features even MORE monsters, it’s high time someone stepped up on this property. Barker’s flagship property, HELLRAISER, had a phenomenal and extensive line of figures through NECA, covering the first four films in the series which means a few variations of Pinhead in the mix. Hell, McFarlane Toys also had Candyman as part of their Movie Maniacs line. But NIGHTBREED, with its monster-heavy cast of characters? Not a one. So to get things started, which characters would make up a hypothetical “first wave”? Protagonists Boone and Lori, obviously. Sharp-dressed serial killer, Dr. Decker, would be a neccesity. Breed members, Peloquin & Kinski (pictured above) and mother-daughter two pack, Rachel and Babette. Round out the set with ex-preacher/ Big Bad In Waiting, Ashberry, and Wave One is a done deal. Future waves could put other characters in the spotlight – the brutish Berserkers, Midian’s lawgiver, Lylesburg, and ebony-skinned devil, Lude, for example. The potential is there. And I’ve wanted a Peloquin figure since 1990…. but I digress…

NIGHTBREED: A”no-brainer” and long overdue. Clive Barker’s 1990 cult classic has been screaming for a toy line for decades. With a newfound appreciation among horror fans, and a restored Director’s Cut that features even MORE monsters, it’s high time someone stepped up on this property. Barker’s flagship property, HELLRAISER, had a phenomenal and extensive line of figures through NECA, covering the first four films in the series which means a few variations of Pinhead in the mix. Hell, McFarlane Toys also had Candyman as part of their Movie Maniacs line. But NIGHTBREED, with its monster-heavy cast of characters? Not a one. So to get things started, which characters would make up a hypothetical “first wave”? Protagonists Boone and Lori, obviously. Sharp-dressed serial killer, Dr. Decker, would be a neccesity. Breed members, Peloquin & Kinski (pictured above) and mother-daughter two pack, Rachel and Babette. Round out the set with ex-preacher/ Big Bad In Waiting, Ashberry, and Wave One is a done deal. Future waves could put other characters in the spotlight – the brutish Berserkers, Midian’s lawgiver, Lylesburg, and ebony-skinned devil, Lude, for example. The potential is there. And I’ve wanted a Peloquin figure since 1990…. but I digress…

William Eigerman , while not as refined and polished as Decker, is cut from the same cloth: a man of violence and toxic masculinity, masquerading as the face of respectability – in this case, Shere Neck’s police chief. Eigerman is a fascist through and through ( his name roughly translates to “Man of Stone) with the one-two punch of “just folks” charm and brute force. His constables, loyal to the last man, eagerly follow their boss’ evry wish, partly out of fear, but mostly out of respect. Eigerman’s relationship with his troops (and presumably with the townspeople)

William Eigerman , while not as refined and polished as Decker, is cut from the same cloth: a man of violence and toxic masculinity, masquerading as the face of respectability – in this case, Shere Neck’s police chief. Eigerman is a fascist through and through ( his name roughly translates to “Man of Stone) with the one-two punch of “just folks” charm and brute force. His constables, loyal to the last man, eagerly follow their boss’ evry wish, partly out of fear, but mostly out of respect. Eigerman’s relationship with his troops (and presumably with the townspeople) But the greatest threat will be found in the least likely of this trinity, the Reverend Ashberry (Malcolm Smith). In many ways, he’s the town fool, openly denigrated by Eigerman, Decker and the assembled mob of The Sons of the Free as weak, “a drunk” and “faggot”. But that all changes when Ashberry is “touched” by Baphomet, The Breed’s god-protector, during The Battle of Midian. Scarred and reconfigured by this encounter, Ashberry is a changed man. Rejected by both his god and The Breed’s, he serves a new purpose: the eradication of The Tribes of The Moon. When the wounded Eigerman begs Ashberry to take him along, the priest snaps his former tormentor’s neck without a second thought and leaves the ruins to fulfill his new destiny. While his story, and The Breed’s, was never continued in cinematic form, Barker had very specific plans for this new enemy, as seen in this passage from NIGHTBREED: THE MAKING OF THE FILM:

But the greatest threat will be found in the least likely of this trinity, the Reverend Ashberry (Malcolm Smith). In many ways, he’s the town fool, openly denigrated by Eigerman, Decker and the assembled mob of The Sons of the Free as weak, “a drunk” and “faggot”. But that all changes when Ashberry is “touched” by Baphomet, The Breed’s god-protector, during The Battle of Midian. Scarred and reconfigured by this encounter, Ashberry is a changed man. Rejected by both his god and The Breed’s, he serves a new purpose: the eradication of The Tribes of The Moon. When the wounded Eigerman begs Ashberry to take him along, the priest snaps his former tormentor’s neck without a second thought and leaves the ruins to fulfill his new destiny. While his story, and The Breed’s, was never continued in cinematic form, Barker had very specific plans for this new enemy, as seen in this passage from NIGHTBREED: THE MAKING OF THE FILM:

Lovecraft done right: The term “Lovecraftian” gets thrown around a lot. More often than not, it’s used as a lazy shorthand for “gooey, with lots of tentacles”. In fact, Lovecraft’s brand of fiction was short on gore or shock value and dealt with more metaphysical concerns – notably, man’s insignificance compared to the vast, unknowable reaches of the beyond. And yes, while THE VOID does have its share of slimy and slithery appendages, it’s firmly rooted in Lovecraft’s ethos: “We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.” Decisions are made that breach the barrier between our world and…well, somewhere else… that have dire consequences for this side of the veil. It also manages to convey one of Lovecraft’s harder tactics: less is more. We see just enough of the otherworldly horrors brought forth from the other side without a grand-full-frame reveal, which only ends up making things more unsettling. We’re also left with no exposition dump on just what exactly is waiting in The Void, building the mystery with nightmare flashes, making the viewer fill in the blanks with their own worst fears. And that is NOT easy to pull off in a visual medium, folks, but they find that sweet spot . Kostanski and Gillespie have made a film that’s worthy of the “Lovecraftian” label. And true to form, shit gets pretty bleak.

Lovecraft done right: The term “Lovecraftian” gets thrown around a lot. More often than not, it’s used as a lazy shorthand for “gooey, with lots of tentacles”. In fact, Lovecraft’s brand of fiction was short on gore or shock value and dealt with more metaphysical concerns – notably, man’s insignificance compared to the vast, unknowable reaches of the beyond. And yes, while THE VOID does have its share of slimy and slithery appendages, it’s firmly rooted in Lovecraft’s ethos: “We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.” Decisions are made that breach the barrier between our world and…well, somewhere else… that have dire consequences for this side of the veil. It also manages to convey one of Lovecraft’s harder tactics: less is more. We see just enough of the otherworldly horrors brought forth from the other side without a grand-full-frame reveal, which only ends up making things more unsettling. We’re also left with no exposition dump on just what exactly is waiting in The Void, building the mystery with nightmare flashes, making the viewer fill in the blanks with their own worst fears. And that is NOT easy to pull off in a visual medium, folks, but they find that sweet spot . Kostanski and Gillespie have made a film that’s worthy of the “Lovecraftian” label. And true to form, shit gets pretty bleak.

Fishburne’s Miller, the captain of The Lewis & Clarke salvage ship, is straight-up, no-nonsense, placing his crew’s safety over all other concerns, even if it means putting himself in jeopardy. And he does it all with an effortless “military man” cool. The other cast members equip themselves well enough, but Neill & Fishburne keep things anchored, especially when in conflict over the mission plan.

Fishburne’s Miller, the captain of The Lewis & Clarke salvage ship, is straight-up, no-nonsense, placing his crew’s safety over all other concerns, even if it means putting himself in jeopardy. And he does it all with an effortless “military man” cool. The other cast members equip themselves well enough, but Neill & Fishburne keep things anchored, especially when in conflict over the mission plan.